(This article was first published with more extensive photographic material in Scottish Local History Issue 96)

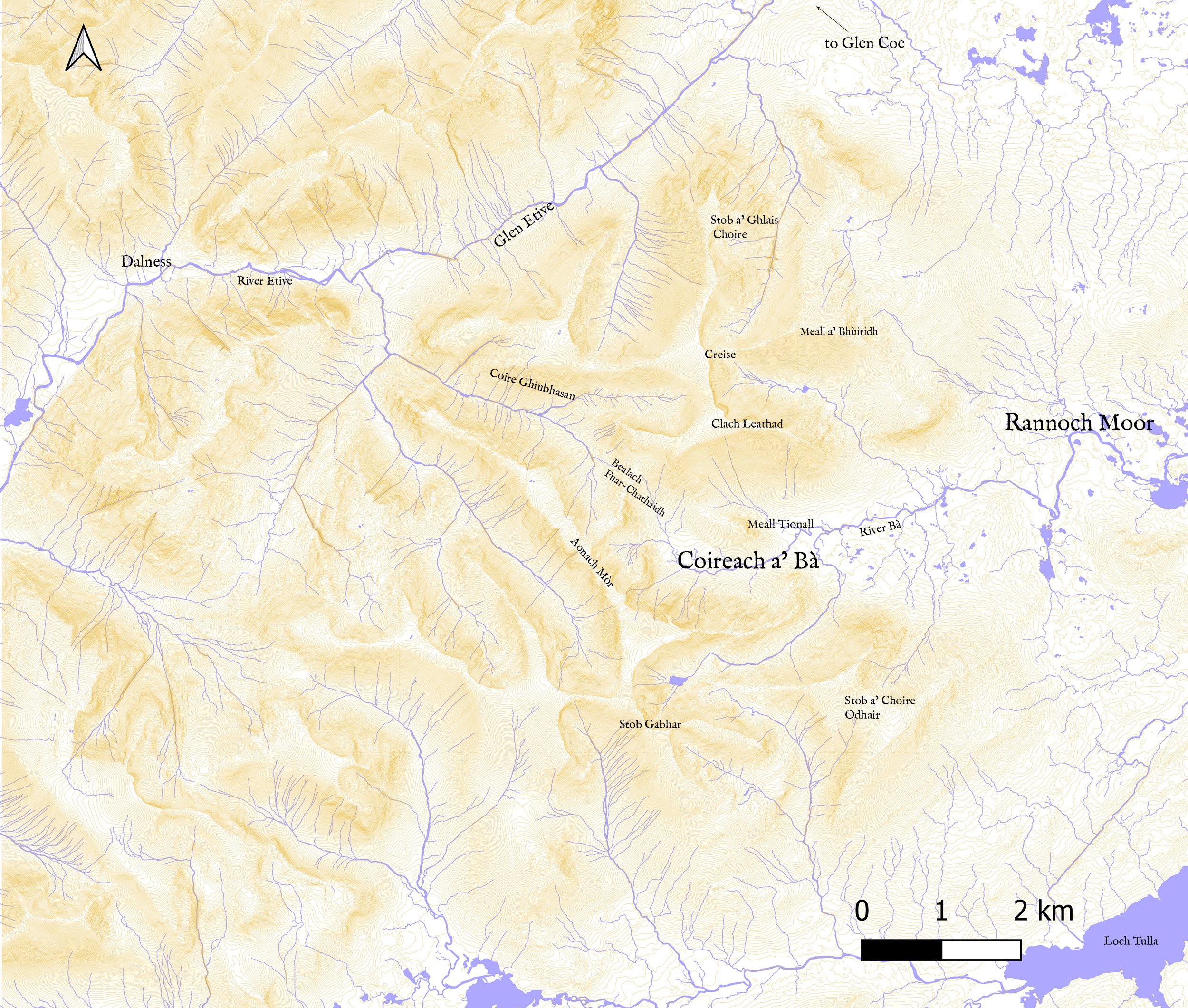

Glenorchy and western Breadalbane were home to deer reserves policed by game herds and foresters in the employ of the Campbells of Glenorchy. This family established its hold over Breadalbane in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and their position as Royal Foresters of Mamlorn was an important element in their status in the region. Mamlorn covered the area around Beinn Heasgarnich between Glen Lyon and Glen Lochay. Its heritable keeping was entrusted to Duncan of Glenorchy in the late 16th century.[i] The family also controlled the hunting around what is now the Black Mount deer forest, including the great Coireach à Ba (the Corrie of the Cattle) which served as another game reserve. These areas were home to herds of Red Deer that the Laird preserved for his and the King’s pleasure (though the monarchy rarely made it so far into the Highlands) and remained in Campbell hands until the nineteenth century.

The Campbells of Glenorchy employed numerous foresters and game herds to manage the land and game in these and other areas. One such forester has left a remarkable legacy of song inspired by his time in the hills of Breadalbane and the Black Mount. Duncan Ban MacIntyre (Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, 1724-1812), born in Glen Orchy, was, at various points in his life, a soldier, forester and city guardsman but first and foremost a lyricist. He is regarded by many as one of the foremost Gaelic bards of his age, and he has left a legacy of work that serves also as a historical resource. His most famous works relate to his time as a forester or gamekeeper, and provide valuable insights for historians of the area and of hunting in the period. Macintyre himself was illiterate. His work was first transcribed and published in 1768, and several editions of collected works followed, until the most recent collection with English translation in 1952.

He had a wide a varied career, encompassing service in the Hanoverian forces during the Jacobite rebellion of 1745-6, and periods of service in the Edinburgh militia. However, it was relatively early, as a forester in the service of the Earl of Breadalbane, that his professional and artistic life came to harmonious fruition in a series of compositions of which Moladh Beinn Dόbhrain (In Praise of Beinn Dorain) is the most substantial and deservedly well known.

His time as a forester came after his military service during which he saw action at Falkirk with the Argyll Militia. His experience of the battle was less than glorious and involved the loss of a sword which was a family heirloom of Archibald of Crannach. He commemorated the defeat (and the loss of the sword) in his song of the Battle of Falkirk (Oran Do Bhlar na h-Eaglise Brice).

Like many Gaels, he appears to have been at ambivalent about the Hanoverian cause, despite serving in the Government army. Amongst other things, he observed the assault on Gaelic culture that accompanied anti-Jacobite policy. He composed a song to King George, but also a Song to the Breeches, (Oran Do ‘n Bhriogais) in which he bewailed the shortcomings of trousers compared to a plaid and tellingly, amongst the humour, declared:

‘S olc an seòl duinn am Prionns’ òg

A bhith fo mhóran duilichinn,

Is Rìgh Deòrsa a bhith chòmhnaidh

Far ´m bu choir dha tuineachas

Dire is our plight that the young Prince

Should be in great adversity,

and that, where he ought to be established,

King George should be the occupant.[ii]

In his later years he also wrote a second Song of the Battle of Falkirk, which again openly declared his Jacobite sympathies.

His career as a forester encompassed periods in Glen Lochay (watching the ancient forest of Mamlorn), Glen Auch (as forester of Beinn Dorain), Loch Tulla (in what is now the Black Mount deer forest) and also a period in the employ of Campbell of Argyll as forester in Glen Etive.

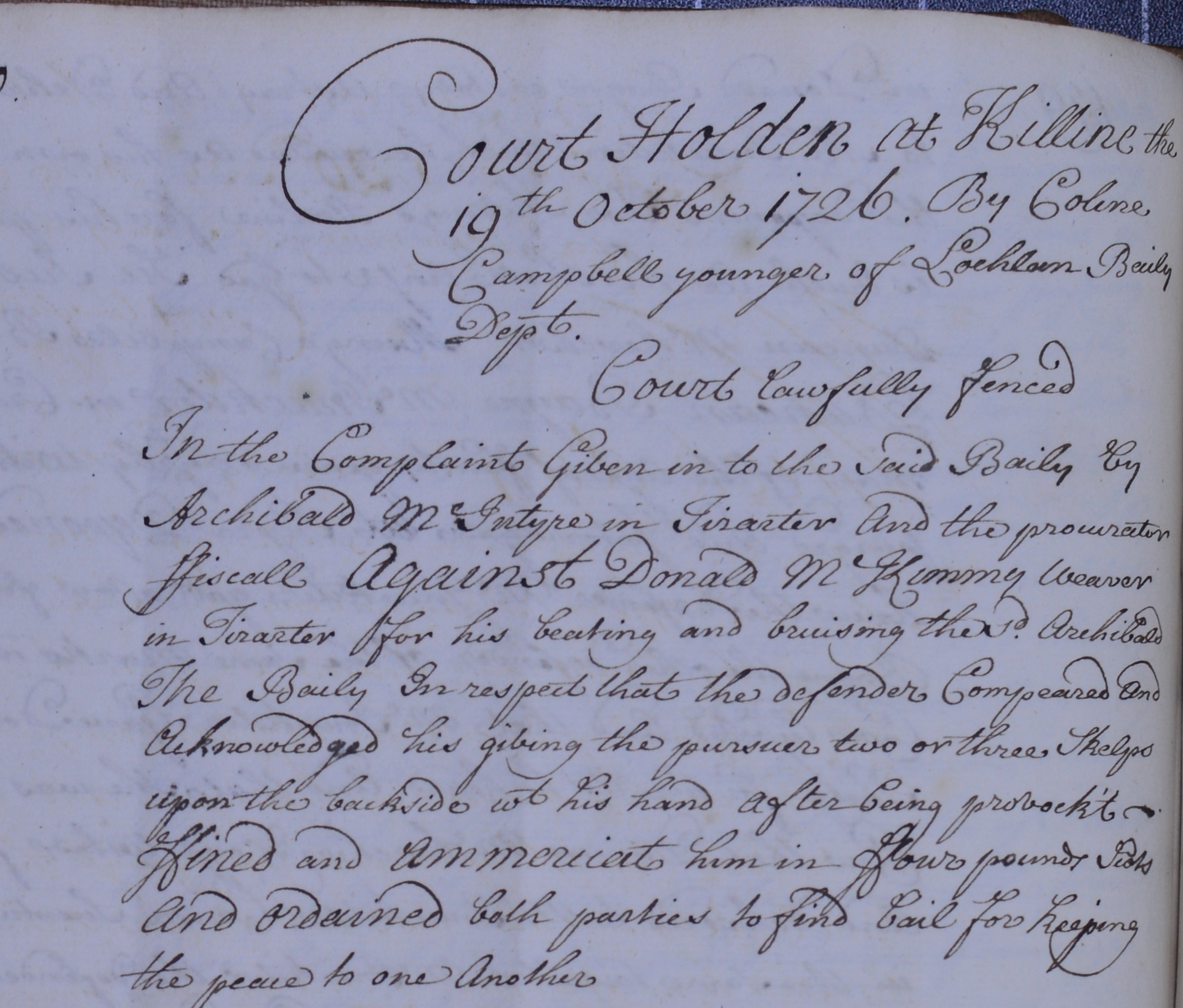

The position of forester was not primarily concerned with what would today be regarded as “forestry”, namely the care and maintenance of woodland for the extraction of timber. Rather, foresters in the seventeenth and eighteenth century were responsible for the care of areas of land that had been designated “forest” or wild land for a variety of purposes. The forester’s duties included the preservation of game, timber and underwood and the enforcement of local byelaws relating to land and natural resources.

Duncan’s heartfelt engagement with the life of the mountains, and his intimate understanding of their flora and fauna, especially in relation to hunting, are clear in his works. For environmental historians these songs are a rich and highly personalised account of the thoughts, feelings and activities of a Gael whose working life was bound up in the land and animals of Breadalbane and Glen Orchy.

His station at Ais-an t-sìthean (the place or haunt of the faeries) at the head of Glen Auch inspired his masterwork, In Praise of Beinn Dorain (Moladh Beinn Dόbhrain). From this vantage point, he could survey most of the places mentioned in the song, which follows a herd of deer over the slopes of the mountain. With the exception of the Lament for the Misty Corrie, his ‘nature’ songs are celebratory, full of the richness of the environment, none more so than his Song of Summer and In Praise of Beinn Dorain. In the latter, he sings of the deer on Beinn Dorain:

’S annsa leam ’n uair théid

Iad air chrònanaich

Na na th’ ann an Eirinn

De cheòlmhoireachd

When they take to crooning,

I like it more

Than all there is in Eire

of harmonies[iii]

He is not, however, beyond killing these creatures whom he adores. Iain Crichton Smith argues that Macintyre’s poetic treatment of the deer is entirely pagan. “Macintyre is not on the side of the deer morally. He loves them, he adores them. He has created them with marvellous fidelity and minuteness of detail”, yet later in the song, he shoots them and releases the hunting dogs that run down these beautiful creatures. This, and other elements of the Macintyre’s work give insights into a world-view that may be “pagan” (as Crichton Smith argues), or might simply reflect an approach to animals and the natural world that had not yet been influenced by an Enlightenment rationalism. The attachment with and personification of the deer is almost erotic – he describes them as “curaideach”, which Crichton Smith translates as “coquettes”. An intimate connection between hunter and prey is not uncommon in many hunting communities, nor is the association of hunting with a form of seduction. These associations suggest a world view different to the Western rationalism of today.[iv]

Macintyre also took pride in his skill as a hunter, and his works provide insights into the technology and techniques of eighteenth century. The finale of Moladh Beinn Dόbhrain describes a form of deer stalking: the pursuit of deer by a single stalker, with the objective of injuring a deer for the animal to be brought down by dogs. Macintyre describes the gun in meticulous detail, even down to the mechanism of the flintlock. The way he narrates the equipment and the technique of stalking speaks of a man who is not only celebrating the hunt, but is also demonstrating his own expertise. He is not, however, without the capacity for humility. His Song on a Hunting Fiasco (Oran Seachran Seilge) commemorates a day of failure on the hill after missing a deer with his shot:

’S mi teàrnadh a Coir’ a’ Cheathaich,

’S mόr mo mhìghean ’s mi gun aighear,

Siubhal frìthe ré an latha:

Thulg mi ’n spraigh nach d’ rinn feum dhomh.

As I descended from Misty Corrie,

great is my dudgeon, I am cheerless,

ranging forest all day long:

I fired the burst that gained me nothing.[v]

The same song also includes the revealing lines:

Ged tha bacadh air na h-armaibh

Ghléidh mi ’n Spàinteach chun na sealga

Though there is a ban on weapons,

I saved the Spanish gun for hunting[vi]

The Disarming Acts meant that firearms were indeed banned in the decades after Culloden, but presumably Macintyre felt safe enough to carry his sporting piece- perhaps with the earl of Breadalbane’s permission. It is also not clear whether Duncan was shooting deer for his own use or for the laird’s. It was common practice from the middle ages onwards that while elaborate hunts involving numerous horses and personnel were undertaken for entertainment, the provision of venison for lordly and royal tables was often left to expert servants who would use quick and efficient methods. It is likely that occasional hunting for the pot was tolerated from the foresters alongside their work to supply the table.

Duncan’s work is rich with references to guns, gunpowder and bullets, so much so that the intimacy with which he engages the animals of the mountain also extends to the means of their destruction. So attached was Duncan to his gun that he even composed a Song to a Gun Named Nic Coiseim (Oran do Ghunna Dh’ an Ainm Nic Coiseim), in which he says, despite his financial straits, he would never sell her:

Ged tha mi gann a stòras

Gu suidhe leis na pòitearan

ged théid mi do ’n taigh-òsda,

Chan òl mi ann an cuaich thu

Though I have scant resources

to sit down with the topers,

yet, though I go into the inn,

I will not drink thee in a cup.[vii]

Duncan’s work gives us a detailed picture of the work of a forester, or gamekeeper, beyond the business of walking the hills. Local politics that came into play: his Lament for the Misty Corrie (Cumha Coire A’ Cheathaich) is a bitter complaint about being ousted from the position of forester at Coire A’ Cheathaich (in the ancient forest of Mamlorn) in favour of a MacEwan who, he says, “is like a stone in lieu of cheese” (mar chlach and ionad càbaig). He catalogues the failings of his replacement: he has driven off the deer with his useless, rusty gun, and has left the woods to go to ruin and the burns have spoiled. This is of course hyperbole, and says more about Macintyre’s complaint than it does about the real business of managing a deer forest, though it does indicate the main areas of responsibility for a forester. Mamlorn was a Royal forest, meaning that the earl himself was, in effect, head forester for the king. Duncan makes reference to this when he concludes his litany of complaint:

Thig gach uile nì g’ a àbhaist,

Le aighear is le àbhachd

’N uair gheibh am baran bàirlinn

Siud fhàghail gun taing

All will revert to use and wont

with mirth and jubilation

when the baron gets a summons

to quit, and has no choice.[viii]

Despite his bitterness at his removal from Mamlorn, it was his subsequent station in Glen Auch that gave us Moladh Beinn Dòbhrain. This, and his other “nature” songs, represent an invaluable resource for the history of our relationship with the landscape and the plants and animals within it. The very personal nature of Macintyre’s descriptions, of hunting methods, landscapes and the animals that populate them, have left us with a detailed and varied picture of hunting and its management in the southern Highlands of the eighteenth century.

This was a period of transition. Older, personnel-intensive hunting methods such as deer drives and elaborate chases with dogs were in decline. Indeed by Duncan’s time, deer drives were a thing of the past. Stalking, originally with bows and later with guns, was a very old, less elaborate method. Duncan’s description of this style of hunting – an individual or small group shooting a deer and having the dogs pursue it – has echoes of poaching undertaken by the young lord of Glenlyon and his servants in the Mamlorn forest in the 1620s.[ix] This kind of hunting required intimate knowledge of the landscape, confident use of firearms, knowledge of animal behaviour and no small amount of luck.

Within Duncan’s lifetime, sheep ranching would come to oust older land use, and his Song to the Foxes (Oran Nam Balgairean) railed against the woolly invaders and congratulated the foxes for taking lambs. Beyond his lifetime, the Highlands would see the explosion of Victorian sporting tourism and, in turn, the development of new deer forests and “sporting estates”. In Duncan’s old stomping grounds the Black Mount deer forest would supplant the ancient game reserve based around Coireach a Bà (“Corrichiba” in many records) and after Duncan’s death the second Marquis of Breadalbane would successfully re-introduce the Capercaillie.

Duncan has documented through his songs an important chapter in the use of land and animal resources in the southern Highlands. What shines through at every turn is his intimacy and pride in his role and expertise as a forester. Perhaps it is best to leave the final word to him, again from Beinn Dorain:

Chan ‘eil muir no tir

A bheil tuilleadh brigh

‘S a tha feadh do chrich

Air a h-òrdachadh

There is neither sea nor land

that has more opulence

than is here disposed

within thy boundary. [x]

Notes and Further reading

This article is written by a historian, not a Gaelic specialist. The original works in Gaelic and their translations in this article are taken from Angus MacLeod’s 1952 edition and translation of all of Duncan Ban Macintyre’s published songs, with additional material from Iain Crichton Smith’s translation of Moladh Beinn Dòbhrain. More recently, Alan Riach has also translated the song.

John Murray, in his excellent guide to Gaelic toponymy, Reading the Gaelic Landscape: Leughadh Aghaidh Na Tire, has traced the route of the deer that Macintyre describes in Moladh Beinn Dòbhrain. This is an example of the intimate descriptive naming of the landscape common throughout the Gaidhealtachdt.

Angus Macleod, trans and ed, The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952

Alan Riach, trans, Praise of Ben Dorain, the original Gaelic text with an English translation, Kettillonia, 2013

Iain Crichton Smith, Duncan Ban Macintyre’s Ben Dorain, Northern House, Newcastle, 1969

John Murray, Reading the Gaelic Landscape: Leughadh Aghaidh Na Tire, Whittles, 2014

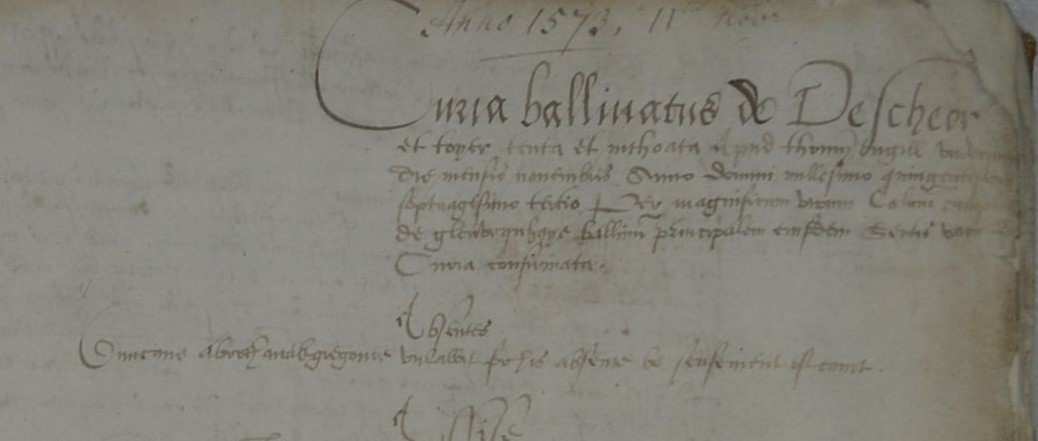

[i] National Records of Scotland, Breadalbane Muniments, MS GD112/59/3/1-5, 8

[ii] Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, ‘Oran Do ‘n Bhriogais’, in The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, trans. and ed. by Angus Macleod, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952, pp8-9

[iii] Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, ‘Moladh Beinn Dòbhrain’, in The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, trans. and ed. by Angus Macleod, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952, pp202-203

[iv] Iain Crichton Smith, “Duncan Ban Macintyre’s Ben Dorain”, Northern House, Newcastle, 1969, pp6, pp12

[v] Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, ‘Oran Seachran Seilge’, in The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, trans. and ed. by Angus Macleod, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952, pp156-157

[vi] ibid

[vii] Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, ‘Oran do Ghunna Dh’an Ainm Nic Coiseim’, in The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, trans. and ed. by Angus Macleod, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952, pp228-229

[viii] Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, ‘Cumha Coire A’ Cheathaich’, in The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, trans. and ed. by Angus Macleod, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952, pp182-183

[ix] National Archives of Scotland, GD112/59/4/7-9, 12

[x] Donnchadh Bàn Mac an t-Saoir, ‘Moladh Beinn Dòbhrain’, in The Songs of Duncan Ban Macintyre, trans. and ed. by Angus Macleod, Sottish Gaelic Texts Society, Edinburgh, 1952, pp220-221